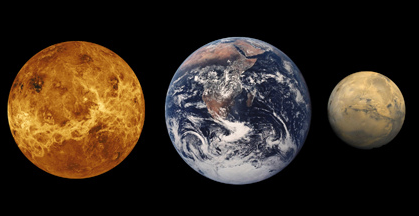

Why Catholics are from Venus and Protestants are from Mars

Asking the question “What is Pope Francis up to?” is something that Catholics and Protestants have in common. After two years of discussions, including two synods (gatherings) of Bishops, Francis has finally spoken on the subject of marriage and the family.

“The Joy of Love” (Amoris Laetitia) has received predictable coverage from the usual suspects: a gay paper OUTnPerth headline is “Pope Francis says the Catholic Church should be less judgmental” while the Sydney Morning Herald pulled out the quote “The erotic dimension of love”.

Amoris Laetitia is an “exhortation” rather than the sort of document known as an encyclical, which would define doctrine. The last encyclical was Laudato Si, which was about dangers to the global environment.

Confronted with a 60,000-word document, the media can be excused for variant readings. As I hope to point out, reading things in different ways may be part of what Pope Francis wants to bring about.

But let’s start with a plain reading of the text. John L. Allen Jr, the doyen of catholic journalists writing on cruxnow.com picks out a key passage.

“Although the 264-page text treats a staggering variety of topics, public interest initially will focus on what Francis says in Chapter Eight about Communion for the divorced and civilly remarried, since that was the lighting rod issue in two contentious Synods of Bishops in 2014 and again in 2015.

“In a nutshell, the Pope neither creates any new law on the issue nor abrogates any existing one.

“What he does do, however, is place great stress on the pastoral practice of applying the law, insisting that pastors must engage in a careful process of ‘discernment’ with regard to individual cases, which are not all alike, and help people reach decisions in conscience about the fashion in which the law applies to their circumstances.”

The practical outworking of this will take place at the local level. In this documents the footnotes are important and one that Allen points to is on page 336: “This is also the case with regard to sacramental discipline.”

In other words, whether a divorced and civilly remarried couple can take part in the Mass will be up to the local priest who will have to talk this through with the couple and decide whether they can take part. (This is because remarriage of people who have been divorced in a court rather than having their marriage annulled by the church on more restricted grounds is not allowed in the Catholic Church.)

This example, as well as being a hot issue in the Synods on the Family, gives us an insight into how the Catholic Church under Francis works.

The Pope is making no change to church law. It is still strictly forbidden, on paper, for civilly remarried couples to take part in the sacraments.

“Amoris Laetitia represents a breakthrough of no small consequence,” writes Allen, “because for once in a Vatican text, what got enunciated wasn’t simply the law but also the space for pastoral practice.”

In the New York Times, Catholic columnist (yes, they have one) Ross Douthat says we are seeing how Pope Francis will balance the competing agendas of liberal and conservative Catholics.

“The question wasn’t just how far he would go in encouraging flexibility. It was how far he could go without hitting a kind of self-destruct button on his own authority, by seeming to change the church in ways that conservative Catholics deem impossible.

“Now we have an answer, of sorts. In his new letter on marriage and the family, the Pope does not endorse a formal path to communion for the divorced and remarried, which his allies pushed against conservative opposition at two consecutive synods in Rome, and which would have thrown Catholic doctrine on the indissolubility of marriage (and sexual ethics writ large) into flagrant self-contradiction.

“But what he does seem to encourage, in passages that are ambiguous sentence by sentence but clearer in their cumulative weight, is the existing practice in many places — the informal admission of remarried Catholics to communion by sympathetic priests.” On this issue and some others (and only a limited number of others) the law stays conservative but liberal practice is encouraged. Douthat thinks that this makes the Church unstable – this centre will not hold.

So back to our headline, which I have modified from the Allen quote below: “One of the standard talks I’ve given on the Catholic lecture circuit for years now focuses on the cultural gap between the Vatican and Main Street USA. Only semi-jokingly, I sometimes title it ‘Rome is from Mars, America from Venus,’ because it does often seem they’re on two different planets.”

Here in Australia, replace ‘America’ with ‘Protestant’, because in this country our denominations other than the Catholics and Orthodox (and a few Pentecostals perhaps) come from Northern Europe, or at least a cold part of it. Where the law is the law.

So for example in the Uniting Church, despite a significant presence of gay ministers, same-sex marriages under Uniting Church rites do not take place (with a few conspicuous exceptions). In the Anglican Church, when a legal case found that ordaining women bishops was legal, certain dioceses (regions) went ahead and chose a woman bishop. Everyone waited until the law was sorted out.

Allen points out; “For Mediterranean cultures, which still shape the thought-world of the Vatican to a significant degree, law is instead more akin to an ideal.”

He uses the obvious example of Italian drivers. He could have added how people park cars in Rome.

Now bear in mind that this is an exercise in journalistic generalisation. When it comes to church laws: Catholics ARE from Mars and Protestants ARE from Venus.

Featured image: ‘Relative sizes of the terrestrial planets’ by Lunar and Planetary Institute, https://www.flickr.com/photos/lunarandplanetaryinstitute/4110039720. Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?