**Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following story contains images of deceased persons.**

Author, educator and Indigenous language consultant John Harris addressed a Bush Church Aid Victoria annual meeting on a topic close to his heart. Harris is the author of One Blood, a landmark study of 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity. He speaks several Indigenous languages and works with Bible Society Australia, consulting on numerous Indigenous Bible translations.

This NAIDOC Week, as Australia celebrates the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, we’ve extracted part of Harris’ talk on the first Aboriginal evangelists.

Thomas Bennelong – the first Aboriginal evangelist

The eagerness of the first Aboriginal Christians to evangelise their own people was evident from the very outset of mission to Indigenous Australia. The first person specifically appointed as a missionary to Aboriginal people was the Wesleyan, William Walker. As a result of his work in colonial Sydney, the first Aboriginal person was converted to Christianity, the son of Sydney’s famous Bennelong.

Walker baptised him Thomas Coke Walker Bennelong in honour of himself and of Thomas Coke, Superintendent of the Wesleyan Missions, who had died en route to Sri Lanka in 1813. Thomas immediately set about evangelising his own people. Walker wrote of him,

He learned to read his Bible in about three months; his attention to class and prayer meetings was very great and encouraging…he collected the young natives of his tribe, to whom he gave an exhortation, which he concluded with prayer…

Sadly, Thomas died afterwards. While we can no longer reconstruct the precise style and content of Thomas Bennelong’s exhortations (or preaching, as we would now call it), there is little doubt that it would have resembled that of his mentor, William Walker who was said to be ‘a preacher of extraordinary power’.

A Wesleyan missionary and a strong evangelical, Walker had a direct biblical approach, based on the Bible narrative and the claims of Jesus. Thomas was obviously inspired by the Bible, which he rapidly mastered in a foreign language and, following the lead of his mentor, we can be certain his sermons were based upon the Bible narrative.

Thomas Bennelong was the first of a long line of Aboriginal evangelists, those remarkable and gifted Aboriginal Christians throughout the continent who quickly accepted the gospel and then rapidly and enthusiastically sought to evangelise their own people. The two influences on their preaching style were the Biblical narrative itself, particularly the Jesus stories, and the forthright presentation of the gospel by evangelical missionary preachers.

The Protestant missions provided a model of the earnest biblical preacher although those Aboriginal people called to the ministry of evangelism were often not given the recognition they deserved. Many of these people should have been ordained into the Christian ministry. One of the failures of mission was the long reluctance to formally recognise Aboriginal people’s gifts and calling. Fortunately, there was a sufficient tradition in some Protestant circles of the lay evangelist, such that the Aboriginal evangelists were mostly encouraged or at least tolerated.

David Unaipon – preaching the Gospel in South Australia

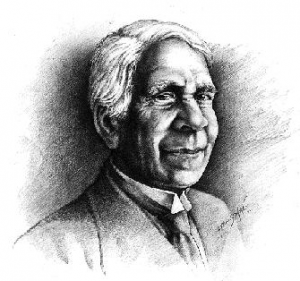

David Unaipon, whose face is on the Australian $50 bill.

The first adult Christian at the Point MacLeay Mission, near the mouth of the Murray River in South Australia, was James Ngunaitponi, a Ngarrindjeri man whose name was Anglicised to ‘Unaipon’ by white people who could not pronounce it.

The mission, technically non-denominational, was conservatively evangelical and ruled by the stern George Taplin. James Unaipon, born about 1830, came to Christ in 1862 through the teaching of a far gentler itinerant missionary, James Reid of the Free Church of Scotland, whose name James took at baptism. He chose to accompany Reid, acting as a translator and taking his own first steps towards evangelism.

Reid was tragically drowned in 1863. In 1864 James settled at the Point Macleay Mission. Taplin was delighted and, to give him his due, he encouraged James to evangelise his own people. James was the first of those Aboriginal evangelists later known in South Australia as the ‘Taplin men’. James learned of other Christian Aboriginal people at other missions and linked up with James Wanganeen of the Church of England Poonindie Mission. Taking with them a young Point Macleay man, William Kropinyeri, they undertook missionary journeys along the Coorong and to other places where the Gospel had not yet been preached.

Better known to Australians was James’ son, David Unaipon, now the face on our $50 bill. An inveterate reader as a child, he grew up to be a remarkably intelligent and learned man with wide academic interests. Entirely self educated, he was a natural scientist, who patented many scientific and technical inventions. He read the classics and could quote huge slabs of Bunyan and Milton. Newspapers dubbed him ‘the black genius’ and ‘Australia’s Leonardo’.

He had an immense knowledge of the Bible, the King James Bible of course, and knew huge sections of it off by heart. He was obsessed with correct English, the English of the classics which he so ardently read and of course the language of the King James Bible.

For his public speaking he developed a pedantic style of oratory which owed more to the classics than it did to current English usage, particularly the broad Australian idiom of rural South Australia. He became quite famous, regularly sought as a speaker in the southern states. He was a political activist in his eccentric own way, a kind of unofficial spokesperson for what he termed ‘Aboriginal advancement’. ‘Look at me’, he used to say, ‘and you will see what the Bible can do’. David Unaipon defied the stereotype of the lazy, ineducable Aborigine and thus made many people uncomfortable.

But with all his talents and eccentric interests, what he loved doing best was preaching the Gospel. A Christian all his life, David Unaipon was a vigorous, outgoing preacher who modelled himself on the forceful, Bible-based style of the missionary preachers who had influenced him. With Aboriginal people he preached in the Ngarrindjeri language but elsewhere he preached in his idiosyncratic brand of English, His sermons were full of Biblical allusions, from the King James Bible of cou

rse, and it was said that he even sounded like the King James Bible.

For all his learning, David Unaipon never lost touch with his Aboriginal roots. He collected and recorded Aboriginal stories. He researched Greek and Egyptian mythology at the South Australian Museum, and came to understand Aboriginal stories as having a similar weight and purpose. He published three books of Aboriginal legends.

In a Christian sense, David’s greatest contribution was in his old age. By the time he was about 80, younger Aboriginal people were taking over the role of campaigning for Aboriginal rights and he was less courted by the influential and the newspapers. He dedicated his final years to evangelism, travelling widely on foot to Adelaide and country towns of South Australia, regularly refused accommodation because of his race and often being detained by the police. David died aged 94, convinced he was about to discover the secret of perpetual motion.

Blind Moses – the faithful preacher at Hermannsburg

Moses Uraiakuraia, an Arrernte (Aranda) man, was about 8 years old in 1877 when the Lutherans established Hemannsburg Mission in Central Australia. Moses was one of the first school pupils. He immediately showed interest in Bible stories and through that interest was keen to learn to read. He was eager to share these stories with others, even as a child, but his people discouraged him from doing this because he was an uninitiated boy and his community did not think him old enough or wise enough to properly evaluate Christian belief and traditional Arrernte belief which he was not yet deemed mature enough to understand.

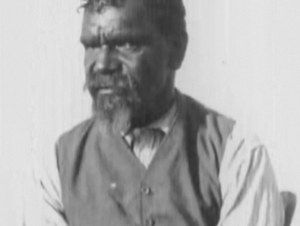

Moses was Central Australia’s first Aboriginal missionary

Although briefly withdrawn from the school, Moses was allowed to return. There he embraced the Christian faith. He was a young man of about 21 years when baptised in 1890.

Shortly afterwards he was taken away by the tribal elders to pass through circumcision and initiation into Arrernte ritual and law. This deeper level of traditional understanding served to confirm Moses’ belief in the God of the Bible, a belief which he firmly held for the whole of his life.

A few years later, Moses became blind and was ever afterwards called Blind Moses. He had people read the Bible to him constantly so that he could learn whole passages by heart. He became a teaching assistant, teaching the Bible. An excellent linguist, he was in continual demand for translating, working closely with the legendary Carl Strehlow on the Arrernte New Testament.

Moses learned the craft of preaching as the interpreter of many missionary’s sermons, but his skill outdid theirs. He was known to markedly improve their preaching. He was a naturally gifted story-teller and became a compelling preacher himself. His style was direct and firmly based in the gospel narrative. Missionary Freidrich Albrecht wrote of him:

I often listened with rapt attention to some of his addresses. To him the New Testament just lives, and he knows how to make it live again before his hearers. To his natural gift he has added a lot of hard work.

Moses’ felt called to evangelise his people, urging the Hermannsburg Christians to go out and share the Gospel with people beyond the mission. He led the way himself, travelling hundreds of kilometres by foot on his wife’s arm or by donkey, preaching in the cattle stations, railway camps and remote desert communities.

In the years when there was no ordained missionary at Hermannsburg, Moses carried the responsibility of evangelism. Indeed, at times such as between 1923 and 1926, with no missionaries at Hermannsburg at all, there was major growth in community acceptance of the Christian Gospel.

This phenomenon has been repeated time and again throughout Australia, the impact of the gospel presented to people by one of their own race and in their own language. Bringing alive the gospel stories was a powerful thing to people for whom all important knowledge was passed on through story-telling.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?