The earliest known draft of the King James Bible has been discovered in Cambridge.

Professor Jeffrey Allan Miller from Montclair State University in New Jersey made the discovery in the archives of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, UK. Two the College’s former Masters were part of the Cambridge-based scholarly team who worked on the King James Bible translation from 1604 to 1611. One, Samuel Ward (1572-1643), is the author of the draft manuscript notebook that Professor Miller discovered.

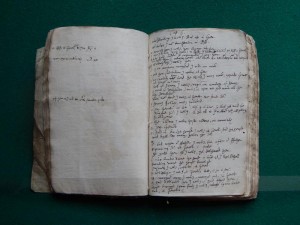

Reproduced by permission of the Masters and Fellows of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. Photo: Maria Anna Rogers.

The discovery of Samuel Ward’s draft notebook has been heralded as a major discovery for what is considered the most significant version of the Bible in history. Speaking to Eternity, David Norton, emeritus professor at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, and a King James Bible scholar and author, said the draft is important “for showing a part of the work on the KJB happening: the scholarship and care that individuals brought to the project…”

Until now, there have been no early drafts of the translation process uncovered for the King James Bible. “The limited nature of what has previously come to light has left a lot to be desired, and many questions unanswered,” wrote Professor Miller in The Times Literary Supplement, where he announced his discovery last week.

To have an early draft of any part of the King James Bible, “unmistakeably in the hand of one of the King James translators”, says Professor Miller, “points the way to a fuller, more complex understanding than ever before of the process by which the KJB, the most widely read work in English of all time, came to be.”

The translation of the King James Bible began in 1604 at the behest of King James I of England. The King commissioned 54 of England’s greatest scholars including Samuel Ward into six teams or “companies”. The teams were to create an “authorised” Bible that would cast off the King’s concerns of anti-royalist margin notes in the first English Bible translation, the Geneva Bible (1560), and would update the later Bishop’s Bible (1568). The Bishop’s Bible was prescribed as the base text for the new King James version.

Professor Miller said Samuel Ward’s papers had been catalogued in the 1980s, including the notebook, which was labelled as a “verse-by-verse biblical commentary…with Greek word studies, and some Hebrew notes”. The part of the Bible referred to by Ward was not specified, and no further study was done.

But when Professor Miller looked more closely at the manuscripts, he discovered it was a sequence of running notes on the translation of the King James Bible’s Apocrypha. The Apocrypha was originally placed between the Old and New Testaments in the first version of the KJB and published with rest of the King James Bible for 274 years, before being removed amid controversy over whether the books were “God-inspired” in 1885.

Examining Ward’s draft, Professor Miller told the New York Times, “You can actually see the way Greek, Latin and Hebrew are all feeding into what will become the most widely read work of English literature of all time,” Professor Miller said. “It gets you so close to the thought process, it’s incredible.”

Professor Miller says one of the most valuable insights offered by Ward’s drafts is the ability to examine the interplay between individual and group translation. It has historically been understood that the King James Bible was translated by members of a team working together. Yet Ward’s draft clearly shows the work of an individual rather than a draft that can be seen as the product of collaboration.

“It forces us to think harder about the extent to which all the companies necessarily set about their work in the same or even a similar way,” said Professor Miller.

“The KJB, in short, may be far more a patchwork of individual translations – the product of individual translators and individual companies working in individual ways – than has ever been properly recognised.”

Professor Norton says Ward’s notebooks suggest that the rules laid down for the translation by King James I were not necessarily followed to the letter, something he has previously suggested in his academic works. “It looks as if Samuel Ward was working as an individual on two particular parts of the Apocrypha,” Professor Norton told Eternity.

But he said he has asked Professor Miller if it’s possible that the work could have been preparatory work for an Apocrypha company meeting. “Such questions matter if we are to reach a clear understanding of the expanding range of evidence about how the KJB was made,” he said.

Nevertheless, the finding is significant, giving scholars the opportunity to look closely at the translation of the Bible that has had, what Professor Norton calls, “unparalleled influence on English-speaking peoples’ religious consciousness, and an influence comparable with Shakespeare’s on the English language.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?